[This is Chap. 16 in the continuing narrative on My Way-finding. Previous chapters are Pages on this site, and links can be found in the menu to the left of the main entry.]

My daddy had a powerful influence on my life.

He was one of those larger-than-life characters who made an indelible impression on everyone, and he shaped me in ways that I’ve only recently begun to understand, though I’ve now outlived him by over a year. He was a tall, handsome man with a personal warmth and a charismatic speaking style that made him the best preacher I ever heard, though he wasn’t a preacher, he was a journalist.

His father and grandfather had both been Baptist preachers, active in the Georgia Baptist Convention and Mercer University, the Baptist college, but Daddy chose a different pulpit: a small-town weekly newspaper. He was a solid Baptist his whole life, and could fill any pulpit with a wonderful sermon, and he raised all of us to be dutiful Baptists as well. I was pretty much into that role until sometime in high school, and college broke me completely out of it (as I’ve related in earlier posts), but that never really came between us at the emotional level.

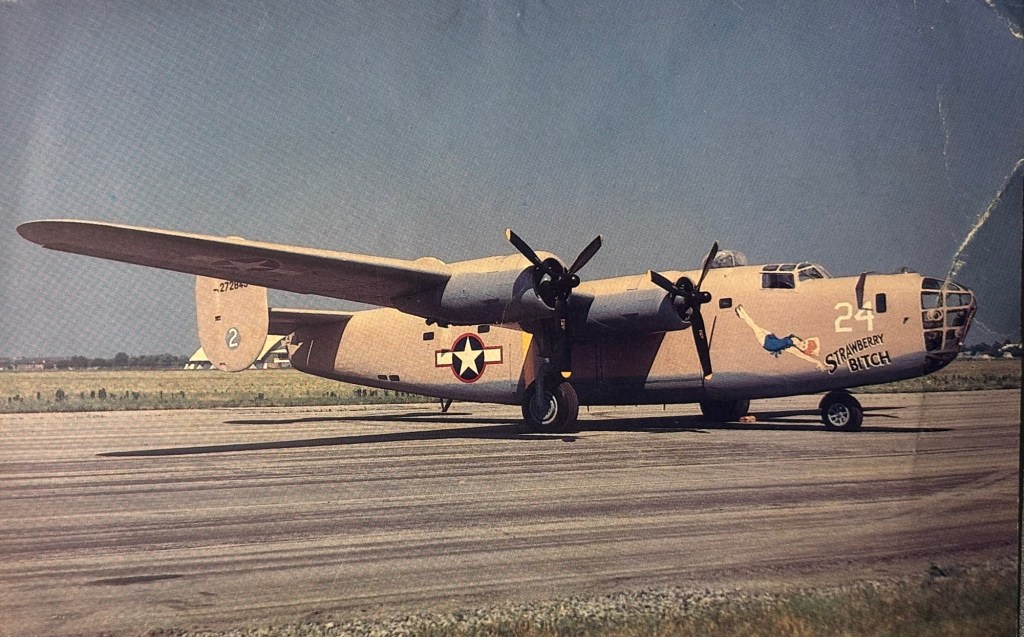

For much of my young life, I wanted to be him, but Vietnam – and all of the Vietnam era radicalism that I embraced – came between us in a big way. He had been a navigator on B-24’s in World War II, flying out of England in the storied raids on Hitler’s ball-bearing factories, and I became a war resister.

Well – first I joined the Air Force and became a pilot because I knew that would make him happy. But then I encountered the reality of the petty little empire-building escapade that we called, in our ignorance and arrogance, “the Vietnam War.” I went, despite my reticence, because I thought I really didn’t know what was going on there, going on in the world, going on in the exalted realms of the U.S. political system… so I should give up my foolish notions of knowing that it was all wrong and just go, like all the other people I knew who had gone and either died or come back.

And then I got there and found out it was every bit as depraved and stupid and immoral and deceptive and wrong as I had thought… and so after about nine months of it, I bailed. At least I tried to. I told them I wasn’t that into the war and wanted to be out of the Air Force.

They said, well, yes, but… no. You haven’t really done anything bad, you’ve played by the rules, been a good boy, so there’s no reason we should let you out before your commitment is up. So then I said, okay, fine, then I won’t do anything for you anymore. By then of course, I was back in the states and supposed to be an instructor, teaching guys to go there and do what I did for a year and ten days. (I was in country an extra ten days waiting for them to decide what to do with me, since I had an “administrative action pending”.)

It’s a long story, one I’ve related in my War Journal, which is on my website hoyama.org, but the upshot is, I finally got out. In the process of this, of course, my father and I had some serious, divisive, but inconclusive, discussions. He never really understood, though my mother supported me, and even after it was all over – my discharge, the war, the social debate – we never really talked about it at the level that we should have.

And then he died.

On his 66th birthday, really in the prime of his life, while I was living in Oregon, he went into heart bypass surgery and never regained consciousness. We rushed back to Georgia when they decided he needed the surgery, but he was still on the machine when we arrived, and his heart would never resume its work on its own, so he died as I stood in the intensive care ward watching him breathe and listening to the machines beep.

….

I was totally unprepared for the loss, and it flattened me.

I was pretty much lost in grief for some time, but eventually I repressed most of it and went back to my ignorance and denial. But it dug a hole in me that began to fester. All those unsaid things began to eat away my insides, All the regret and guilt of a lifetime eventually ate away my heart and my gut and replaced them with balls of molten metal.

About a year after Daddy’s death, Giana and Luke and I moved back to Georgia to be with my mom. She had been left pretty much alone when Daddy died, and though she was a strong and independent woman in many ways, the solitary life didn’t suit her. She needed family around, so we came.

Moving back to Georgia, I figured any hope of ever finding a Buddhist group to be part of was over. It was Georgia, the heart of Baptist-land. But I brought my Buddha-rupa, my carving, and set up a low-key altar in my house. I continued to think of myself as a Buddhist and read books about Buddhism.

And those balls of hot iron continued to grow inside me. I continued to descend into depression in longer and deeper spirals. I had never figured out that I needed to meditate on a regular basis. It seemed more like an exotic delicacy to be tasted at random, when in fact it’s as necessary as daily bread. So I suffered, and I visited that suffering on all those around me.

….

And then one day, our friend Claire came home from a weekend in Atlanta and told me about this wonderful thing she had found: a Zen center.